This document is part of a series. Select the image(s) to download.

Published Manuscript

Vom Werden in unsrer Jugend Inselsberg – Grossenheidorn - Schlüchtern (The Movement among Our Young People)

EA 20/12

| Additional Information | |

|---|---|

| Author | Eberhard Arnold |

| Date | May 01, 1920 |

| Document Id | 20125978_13_S |

The Movement among Our Young People

[Arnold, Eberhard and Emmy papers – P.M.S.]

[Draft Translation by Bruderhof Historical Archive]

EA 20/12

The Movement among Our Young People

Inselsberg – Grossenheidorn - Schlüchtern.

By Eberhard Arnold, 1920

On March 20, 1920, about fifty young people from the most varied areas of our fatherland came together on the Inselsberg [Insel Mountain] in Thuringia lively boys and girls of the Wandervogel [birds of passage] movement in their familiar Free German garb, with no more than a sprinkling of urban or bourgeois types. Startling and novel for some was the sudden bursting in of our young proletarians in their Russian style apparel and luxuriant growth of hair. In their whole bearing and conduct we sensed the refreshing air of the open road, and in actual fact most of them were about to go on the tramp. But also the seemingly so uniform hiking wear of the others could not disguise the fact that those who met here came from very different circles and groups of the youth movement.

In all of them the spirit of freedom is struggling to find new forms, with no group dependent on another or willing to submit to a domineering influence from another. That which all the directions represented here have in common is the will to autonomy, the independent conscience that struggles for truthfulness, for unity of life, and for the realization of an all-embracing love. They are united in the feeling that any forms and expressions not really springing from one's own inner experience must be given up. They are united in turning away from a decadent civilization, in rejecting a doomed form of society and politics. They are united in the pacifist and socialist will to take a stand in and with the proletariat for peace among all men and for opening up to all a truly human existence in all areas of life. The numerous small circles here represented find that this sought for renewal of an ailing humanity, this longed for re-structuring of personal and social life is in some way given to them in Jesus. And this in such a manner that the divine and the experience of Christ is perceived as immediately present in one's own heart and therefore as an absolute commitment, not subject to modification by existing conditions. At bottom, it is a religious unity based on an inner certainty. In this certainty one is deeply convinced that the Spirit of Jesus can only have a freeing effect and that His freedom must come to expression in the love characteristic of Him a love that means living community and joyful work.

For this reason, as already stressed in the invitations sent out, at the Inselsberg gathering there could be no question of an organizational fusion of the different groups. For of necessity such a fusion would in some way have meant a tying down or a hindrance to their future development. It could only be a question of the various spiritual entities' getting to know and stimulating each other, of a mutual exchange and enlivening. Now as before, the individual circles and groups, free outwardly and inwardly, free also from each other, must go on living their own life. The differences between these various groups were clearly noticeable throughout the conference. The friends from the federation of revolutionary youth found the college graduates' manner of talking and speaking often unbearable, as well as the formality of the bourgeois style, which, in spite of everything, still clings to them. For these young revolutionaries only action and nothing but action was of any importance. And we who come from that other world only too often give them the impression that with us notions and notional discussions, words and ever more words take the place of life, and life, after all, cannot be pressed into words. Among those coming from the Free German Youth there were some who, in concert with the Quakers present, wished to pass on to others the specifically Quakerish faith and inwardness. Others from the same circle issued a call to leave behind immediately bourgeois occupations and urban civilization and take to tramping, to wandering or to settlement life in order to thus find the way to themselves, to Christ, and to prophetic mission. ¬Still others are seeking a syncretistic mysticism, in which all other religious spirits are accorded equal rank with Christ. A voice from the Neuwerk (New Work) circle called for objectivity, declaring that it is the cause that matters and not we, that the important thing is not that we live but that we are being lived -¬indeed, that God's wagon keeps rolling on, while all we can do is march resolutely behind it. Next, there were inwardly liberated groups stemming from high school Bible circles, from the German Christian Student Movement and similar associations, who professed their faith more or less dogmatically colored- ¬in the indwelling crucified and risen Christ, the organic unity of the mystical body of Christ and the future Kingdom of God on earth. On the political level, some inclined towards a majority socialism of a moderate kind, which from an economic point of view wants to indiscriminately affirm mankind as a brotherly community. Others favored the communism of the German Communist Party, still others an anarchical communism that looks forward to seeing family associations and life communities, inwardly coherent and growing closer together, build themselves up organically into a new national unity and a unity of all mankind.

The tragic tension that was bound to result from a gathering of such polarized elements often brooded over the meetings like an oppressive thunder cloud. It was also the deepest ¬reason for the phenomenon, confirmed by many, that a certain time had to elapse before people could become aware of the exceptionally strong positive result of the conference. It became clear to us that we are standing before a tremendous religious event that is bound to take place. We are still waiting for a strong religious personality capable of bringing Christ so close to the hearts of all who seek and struggle as if He were living and dying among us, so that we have to live His life just as He lived it. We feel our own religious weakness. But we do notice with unfailing certainty that God is at work to bring about something unspeakably great. And we feel that He is at work within us to prepare the ground for that which is to come.

It was in accordance with this deep going impression that for the time being there could be no thought of a general rally of the Christian youth of all Germany. Quite apart from the fact that the term "Christian" was rejected by some as no less fraught with mammonism, blood, and hatred than the word "Church", a large rally bringing together such a many faceted and ill balanced assortment of young people could only result in ungenuineness or divisiveness. Instead, the Inselsberg experience caused the individual groups to draw together and live together all the more intensively in their own circles. Side by side with smaller gatherings taking place in the various regions of our country, where Quakers, Free Germans, pacifists, socialists, revolutionaries, Bible circle members, and others forgathered in the one religious spirit, the conferences of the "Grossenheidorners" in Grossenheidorn and Bückeburg, of the "Schlüchterners" in Schlüchtern, and of the "Erfurters" in Thuringia were being prepared.

Grossenheidorn and Bückeburg were the scene of a conference of young people from high school Bible circles, at which the youngest ones, too, were able to express themselves. Here, therefore, side by side with working men's problems and the attitude to be taken to existing conditions, it was above all the school question and the issue of life style that were being considered again as seen from the viewpoint of a life directed by the Spirit of Christ. Here, even more than on the Inselsberg, it was emphasized that what is so strongly stirring now is a definite sense and awareness of something new coming into being, which, however, cannot yet be put into words. Any words, such as, e.g. a "living Christianity grounded in love" were felt to be weak and inadequate, in the same way as life is different from the scientific and philosophical books describing it. Life is what matters nothing but life. The only distinction one knows is that between death and life. What came here more strongly to expression than on the Inselsberg was joy in nature, the close harmony between one's personal religious life and an inner openness for creation and for the beauty of landscape with its springing green, also music, circle games, and folk dancing as natural expressions of the vibrant sense of togetherness. From the very beginning, philosophical, theological, and purely political trains of thought were vigorously rejected, as soon as they wanted to raise up their Hydra like heads. All the more powerful was the sense of inner coherence and the awareness that the Spirit of Christ was at work and held sway. The love of Christ, His justice and freedom was powerfully felt, as one faced up to the issues under consideration, especially socialism and pacifism. Behind Plato's spirituality and behind his Eros, behind Zarathustra's going out among men the all-¬pervasive Christ was perceived, before whom all will one day bend their knees. In Christ, one wanted to embrace Francis of Assisi's love to brother fire and brother water, to birds and beasts, as well as Zarathustra's love to his lion, his eagle, and his serpent. One must needs hold fast to Jesus's love to the lower man, but at the same time love to the higher man and to superman had to be seen as fulfilled in Christ.

At Whitsun now the youth groups of the New Work Land Community together with other inwardly liberated circles from Hesse, from southern Germany and other areas, as well as a number of groups from the Free German movement, where hearts have been touched by Christ, and from the proletariat want to meet for a further four days' conference at Schlüchtern. Here, too, people hope by sharing a common experience in a setting of togetherness and of closeness to nature to find hours of inner quiet, and during these times spent in close touch with nature and fellow human beings they want to concern themselves with the mystery of becoming true men, as well as with their position in society, nation, and mankind. They hope to be given a deepened and strengthened impression of what a Christian looks like who is no caricature of either Christ or man. What they are looking for is that fusion of the natural and the super natural, that union of the two realities of life that in our time has taken shape in so few individuals. They know that men of the lower kind, guided merely by the urgings of their natural instincts, are not yet Christians. But they also know that men of a so called higher or nobler type, who have exchanged their instinctive certainty for moralistic principles, traditional prejudices, and dogmatized authorities are just as far or even farther from the Kingdom of God. Only those persons in whom a new instinct, namely religious intuition and inspiration, and a new set of urges, namely a being driven by the Holy Spirit, have become a second nature, a new nature only such persons are accepted by the young people of today as men, as true Christ-like men. The central issue is once again the proclamation of rebirth, the becoming as children through Jesus, release from degeneration and law, and the gaining of true life after losing the false one. And if there are many who regard this way as too subjective and too subjectivist, the reply can only be that the Spirit by whom young people long to be filled, is the all-embracing Creator Spirit, who frees men from their small ego, and that the new man here perceived as the goal is the Christ who gathers all under Himself as the Head. Hence, such an intensification of individualism means ever again a breakthrough to a universalism and communism that is liberated from man's ego.

For this reason, the sounder elements among today's youth can in no way despise or deprecate the active working of the Christ life among the older generation or in circles of a different character. It must be impossible for them to say of an association like the German Student Christian Movement that it is dead. The German S.C.M. is not dead. It is true that as a body it has not yet found a positive relationship to the new life now springing up and this can have disastrous consequences for its future; nevertheless, the living Christ is so strongly at work within it that one would have to be blind to write it off as wholly devoid of life. It must be admitted, though, that what is alive in it is too exclusively personal in character. On the whole, it is a struggle for individual salvation and no more; the early Christian vision of God's all-encompassing activity, of the coming of His Kingdom is but seldom attained. The words of Jesus are taken seriously in a personal sense, but only in rare cases does one dare to apply these words according to their spirit and meaning to the totality of life relationships. In many instances, this often weakly concern with nothing beyond one's own salvation through inwardly experienced grace simply results from a fear of legalism and of mere moralism. I therefore stand against the above mentioned judgment by Karl Udo Iderhoff (in the "Erfurter Führerblaetter", Spring 1920) just as firmly as I stand against a number of currently popular pronouncements against our Christian youth associations. People who regard the moral tendency as the essence of our Young Men's Christian Associations and our fellowships do not know them. Certainly, to the extent that they have a moralizing effect, they form an obstacle to the liberating Spirit of Christ and some of them have indeed grown increasingly rigid to the point where they represent form and tradition, morality, and authority more than the free Spirit who entrusts everything to God and lets Christ do everything. Certainly, in many respects the honor of God and the mighty approach of God's Kingdom have receded behind one's own all too petty soul. Yet, having experienced the powerful times of first love in the Young Men's Christian Associations and in many an inwardly liberated fellowship circle, one knows that something is truly alive in them and that they often contain a rich, many sided life nourished by God and directed towards His Kingdom.

For the young people of our day it will be important to find a positive relationship to that which is alive here and there in societies and associations, in fellowships of all kinds and also in Churches. Freedom from the old forms, liberation from all that is untrue and ungenuine in outward authority and tradition all this can yet go together with a respect for, and acknowledgment of, whatever other living manifestations of God's working one meets, also if they take different forms, just as the early Christian freedom always emphasized the variety of spiritual gifts. One thing, however, is clear: the present day movement can no longer be made to submit to a yoke of servitude or to anything obstructing the flow of its inwardly surging and pulsing life. It is and remains revolutionary in the sense of a true building up of something new.

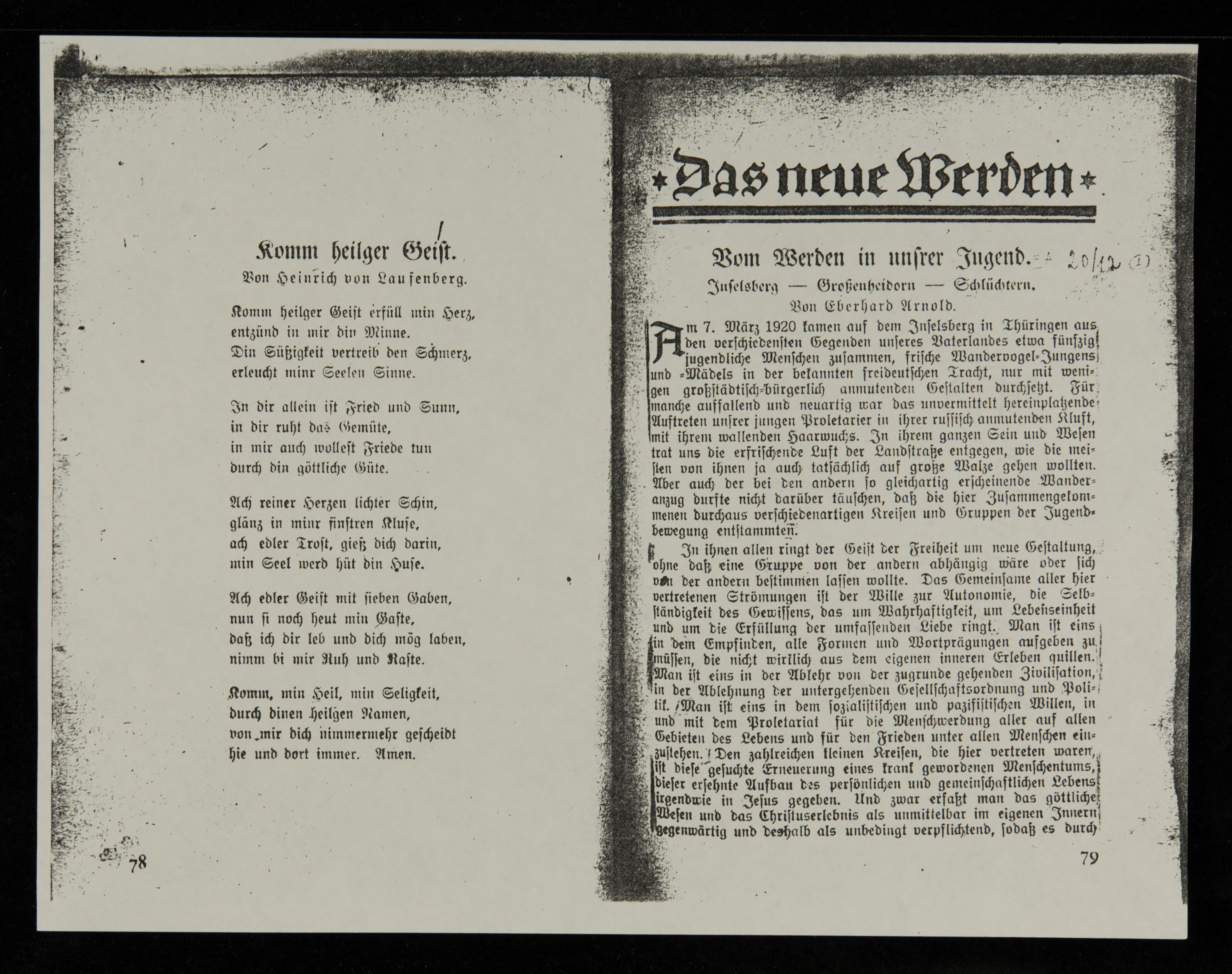

Vom Werden in unsrer Jugend Inselsberg – Grossenheidorn - Schlüchtern

[Arnold, Eberhard and Emmy papers – P.M.S.]

EA 20/12

Das neue Werden

Vom Werden in unsrer Jugend

Inselsberg – Grossenheidorn - Schlüchtern

von Eberhard Arnold

Am 7. März 1920 kamen auf dem Inselsberg in Thüringen aus den verschiedensten Gegenden unseres Vaterlandes etwa fünfzig jugendliche Menschen zusammen, frische Wandervogel-Jungens und Mädels in der bekannten freideutschen Tracht, nur mit wenigen großstädtisch-bürgerlich anmutenden Gestalten durchsetzt. Für manche auffallend und neuartig war das unvermittelt hereinplatzende Auftreten unserer jungen Proletarier in ihrer russisch anmutenden Kluft, mit ihrem wallenden Haarwuchs. In ihrem ganzen Sein und Wesen trat uns die erfrischende Luft der Landstraße entgegen, wie die meisten von ihnen ja auch tatsächlich auf große Walze gehen wollten. Aber auch der bei den andern so gleichartig erscheinende Wanderanzug durfte nicht darüber täuschen, daß die hier Zusammengekommenen durchaus verschiedenartigen Kreisen und Gruppen der Jugendbewegung entstammten.

In ihnen allen ringt der Geist der Freiheit um neue Gestaltung, ohne daß eine Gruppe von der andern abhängig wäre oder sich von der andern bestimmen lassen wollte. Das Gemeinsame aller hier vertretenen Strömungen ist der Wille zur Autonomie, die Selbständigkeit des Gewissens, das um Wahrhaftigkeit, um Lebenseinheit und um die Erfüllung der umfassenden Liebe ringt. Man ist eins in dem Empfinden, alle Formen und Wortprägungen aufgeben zu müssen, die nicht wirklich aus dem eigenen inneren Erleben quellen. Man ist eins in der Abkehr von der zugrunde gehenden Zivilisation, in der Ablehnung der untergehenden Gesellschaftsordnung und Politik. Man ist eins in dem sozialistischen und pazifistischen Willen, in und mit dem Proletariat für die Menschwerdung aller auf allen Gebieten des Lebens und für den Frieden unter allen Menschen einzustehen. Den zahlreichen kleinen Kreisen, die hier vertreten waren, ist diese gesuchte Erneuerung eines krank gewordenen Menschentums, dieser ersehnte Aufbau des persönlichen und gemeinschaftlichen Lebens irgendwie in Jesus gegeben. Und zwar erfaßt man das göttliche Wesen und das Christuserlebnis als unmittelbar im eigenen Innern gegenwärtig und deshalb als unbedingt verpflichtend, sodaß es durch

- - -

die gegebenen Bedingtheiten nicht verändert werden kann. Es handelt sich letzten Grundes um eine religiöse Einheit innerer Gewißheit. In dieser Gewißheit ist man davon durchdrungen, daß der Geist Jesu nur befreiend wirken kann, und daß sich seine Freiheit in der ihm eigenen Liebe betätigen muß, die lebendige Gemeinschaft und werkfrohe Arbeit bedeutet.

Deshalb konnte es sich auf dem Inselberg, wie schon die Einladung betonte, keinesfalls um einen organisatorischen Zusammenschluß der verschiedenen Gruppen handeln. Denn dieser hätte irgend eine Bindung oder irgendeine Hemmung für die zukünftige Entwicklung bedeuten müssen. Es konnte sich nur um ein gegenseitiges Kennenlernen und Befruchten der verschiedenartigen geistigen Wesenheiten, um gegenseitigen Austausch und um gegenseitige Anregung handeln. Die einzelnen Kreise und Gruppen müssen nach wie vor frei von außen und innen, frei auch von einander auch fernerhin ihr eigenes Leben leben. Die Unterschiede zwischen diesen verschiedenartigen Gruppen waren die ganze Tagung hindurch deutlich erkennbar. Die Freunde, die aus der Föderation der revolutionären Jugend kamen, empfanden das Sprechen und Reden der Akademiker und die trotz allem noch anhaftende Formalität des bürgerlichen Wesens vielfach als unerträglich. Für sie galt nur die Tat und nichts als die Tat. Und sie haben bei uns, die wir aus der anderen Welt kommen, nur allzu oft den Eindruck, daß Begriffe und begriffliche Diskussionen, Worte und immer wieder Worte anstelle des Lebens treten, das doch durch Worte nicht gefaßt werden kann. Unter denen, die aus der freideutschen Jugend kamen, wollten die einen im Verein mit den anwesenden Quäkern die spezifisch quäkerische Gläubigkeit und Innerlichkeit weitergeben, - die anderen zum sofortigen Verlassen des bürgerlichen Berufslebens und des städtischen Zivilisationslebens auffordern, um auf der Walze, auf der großen Fahrt oder in der Siedlung zu sich selbst, zu Christus und zur prophetischen Sendung zu kommen, und wieder andere eine religionsmischende Mystik suchen, in welcher neben Christus alle anderen religiösen Geister gleichberechtigt erschienen. Aus dem Neuwerkkreise wurde die objektivisierende Stimme laut, daß es nicht auf uns, sondern auf die Sache ankommt, nicht darauf, daß wir leben, sondern, daß wir gelebt werden, nur darauf, daß der Wagen Gottes läuft, wobei wir diesem Wagen nur entschlossen nachmarschieren könnten. Aus den innerlich befreiten Gruppen, die den Bibelkreisen an höheren Lehranstalten, der Deutschen Christlichen Studentenvereinigung und ähnlichen Verbänden entstammen, wurde ein mehr oder weniger dogmatisch gefärbtes Bekenntnis zu dem innewohnenden gekreuzigten und auferstandenen Christus, zu der organischen Einheit des mystischen Leibes Christi und zu dem zukünftigen Reich Gottes auf der Erde laut. In politischer Hinsicht neigten manche mehr zu

- - -

einem gemäßigten Mehrheitssozialismus, der die Menschheit nach ökonomischen Gesichtspunkten unterschiedslos als Brudergemeinschaft bejahen will, andere zum Kommunismus der K.P.D., wieder andere zum anarchistischen Kommunismus, der den organischen Aufbau der innerlich zusammengehörigen und zusammenwachsenden Familienverbände und Lebensverbände zu einer neuen Volkseinheit und Menschheitseinheit erwartet.

Die tragische Spannung, die sich aus einem solchen Zusammensein so polar entgegengesetzter Elemente ergeben mußte, lagerte oft wie gewitterschwanger über den Zusammenkünften. Sie war auch der tiefste Grund für die von vielen bestätigte Erscheinung, daß das ungemein starke positive Ergebnis der Tagung erst nach einem gewissen Zeitabstand bewußt werden konnte. Es wurde uns deutlich, daß wir vor einem gewaltigen religiösen Ereignis stehen, das unbedingt kommen muß. Wir haben noch nicht die starke religiöse Persönlichkeit, die allen den Suchenden und Ringenden den Christus so ins Herz bringt, als lebte und stürbe er unter uns, so daß wir sein Leben leben müssen, gerade wie er es gelebt hat. Wir fühlen unsere eigene religiöse Schwäche. Aber wir merken es mit unfehlbarer Sicherheit, daß Gott am Werk ist und etwas unerhört Großes schafft. Und wir fühlten es, daß er in uns selbst auf dieses Kommende hin wirksam ist.

Es entsprach diesem tiefgrabenden Eindruck, daß ein gemeinsamer christlicher Jugendtag Groß-Deutschlands für die nächste Zeit nicht geplant werden konnte. Abgesehen davon, daß manche das Wort "christlich" als ebenso mit Mammonismus, Blut und Haß belastet ablehnten, wie das Wort "kirchlich", könnte ein großer Jugendtag so mannigfaltigen unausgeglichenen Lebens nur unecht oder zersprengend wirken. Dagegen mußten infolge des Inselberges die einzelnen Gruppen umso intensiver in ihren Kreisen zusammenkommen und zusammenleben. Abgesehen von den kleineren Treffen in den verschiedenen Gegenden des Vaterlandes, in denen sich Quäker, Freideutsche, Pazifisten, Sozialisten, Revolutionäre, Bibelkränzler, Treubündler und andere in dem einen religiösen Geist zusammenfanden, wurden die Tagungen der "Großenheidorner" in Großenheidorn und Bückeburg, der "Schlüchterner" in Schüchtern und der "Erfurter" in Thüringen vorbereitet. In Großenheidorn und Bückeburg fand ein Jugendtreffen statt, das dem Ursprung aus dem Bibelkränzchen entsprechend auch die Jüngsten zur Geltung brachte. Infolge-dessen wurde hier neben den Arbeiterfragen und neben der Stellungnahme zu dem Bestehenden vor allem die Schulfrage und die Lebensgestaltung ins Auge gefaßt, - wiederum unter die Frage des Lebens aus dem Geist Christi gestellt. Hier betonte man noch stärker als auf dem Inselsberg, daß das große Werden ein bestimm-

- - -

tes Wissen und Ahnen des Neuen sei, das aber noch nicht in Worten ausgedrückt werden könne. Alle Worte wie etwa die von der "lebendigen Christlichkeit aus Liebe" empfand man so tief als schwächlich und unzulänglich, wie das Leben sich unterscheidet von den naturwissenschaftlichen und philosophischen Büchern, die es beschreiben. Um das Leben, um nichts anderes als das Leben geht es. Nur einen Unterschied kennt man, nur den zwischen Tod und Leben. Die Freude an der Natur und der innige Zusammenklang des persönlichen, religiösen Lebens mit der inneren Aufnahme der Schöpfung und der Landschaft in ihrem sprießenden Frühling, auch das Spielen und Tanzen als natürlicher Ausdruck der inneren Schwingung des Gemeinschaftsgefühls trat hier stärker hervor als auf dem Inselberg. Die philosophischen und theologischen und rein politischen Gedankengänge wurden von Anfang an energisch ausgeschaltet, sobald sie ihre Hydra-Häupter erheben wollten. Dagegen war das Gefühl des inneren Zusammenhangs und das Bewußt- sein des waltenden und wirkenden Christusgeistes um so stärker. Die Liebe des Christus und seine Gerechtigkeit und Freiheit wurde allen schwebenden Fragen, besonders dem Sozialismus und Pazifismus gegenüber stark empfunden. Man sah hinter Platos Geistigkeit und auch hinter seinem Eros, hinter Zarathustras Gehen unter die Menschen den alles durchwirkenden Christus, vor dem einst alle huldigen werden. Man wollte mit Franz von Assisi die Liebe zum Bruder Feuer und zum Bruder Wasser, die Liebe zu den Vögeln und zu den Tieren ebenso in Christo umfassen wie die Liebe Zarathustras zu seinem Löwen, zu seinem Adler und zu seiner Schlange. Man mußte naturnotwendig die Jesus Liebe zu dem niederen Menschen festhalten, zugleich aber die Liebe zum höheren Menschen und zum Übermenschen in Christus erfüllt schauen.

In Schlüchtern wollen nun zu Pfingsten die Jugendkreise der "Neuwerklandgemeinde" mit anderen innerlich befreiten Kreisen aus dem Hessenland, aus Süddeutschland und aus anderen Gegenden, sowie manche Gruppen aus dem von Christus bewegten Freideutschtum und aus dem Proletariat zu einem weiteren viertägigen Treffen zusammenkommen. Auch hier will man in dem gemeinsamen Erleben in der Natur und in der Gemeinschaft Stunden der Besinnung finden, in denen das Geheimnis der Menschwerdung in dem Erlebnis der Natur und des Mitmenschen, die Stellung in Gesellschaft, Volk und Menschheit ins Auge gefaßt werden soll. Man hofft einen vertieften und verstärkten Eindruck davon zu erhalten, wie ein Christenmensch aussieht, der keine Karikatur des Christus und keine Karikatur des Menschen ist. Man sucht jene Vereinigung des Natürlichen und des Übernatürlichen, jene Einheit der beiden Wirklichkeiten des Lebens, die heute in so wenig Persönlichkeiten Gestaltung gefunden

- - -

hat. Man weiß es, daß die niederen Menschen, die nur von dem Triebleben ihrer natürlichen Instinkte geleitet werden, noch nicht Christenmenschen sind. Aber man weiß auch, daß die sogenannten höheren Menschen, die ihre Instinktsicherheit zugunsten moralistischer Grundsätze, traditioneller Vorurteile und dogmatischer Autoritäten verloren haben, ebenso fern oder weit ferner vom Reiche Gottes sind. Nur die Menschen, in denen wieder ein Instinkt, nämlich die religiöse Intuition und Inspiration, in denen wieder ein Triebleben, nämlich das Getriebenwerden durch den heiligen Geist, zur Natur, nämlich zur neuen Natur geworden sind, gelten der neuen Jugend als Menschen, als Christusmenschen im wahren Sinne des Wortes. Es ist wieder die Verkündigung der neuen Geburt, es ist das Kindwerden durch Jesus, es ist wieder die Erlösung von Entartung und Gesetz, es ist das Gewinnen des wahren Lebens nach dem Verlust des verkehrten, worum es sich handelt. Und wenn vielen dieser Weg zu subjektiv und zu subjektivistisch erscheint, so kann darauf nur geantwortet werden, daß der Geist, von dem man hier erfüllt werden will, der allumfassende, vom kleinen Ich befreiende Schöpfergeist ist, daß der neue Mensch, der man hier werden will, der Christus ist, der alles unter sich als das Haupt bringt. Deshalb bedeutet eine solche Steigerung des Indiviualismus immer wieder das Durchdringen zu einem vom Selbst befreiten Universalismus und Kommunismus.

Deshalb kann auch die neue Jugend in ihren gesunderen Elementen das lebendige Wirken des Christuslebens in den älteren Generationen aber in andersartigen Kreisen keinesfalls verachten oder gering schätzen. Es muß ihr unmöglich sein, von einer Vereinigung wie etwa der Deutschen Christlichen Studenten- vereinigung zu sagen: "Die D.C.S.V. ist tot" Das ist die D.C.S.V. nicht. Wohl hat sie in ihrer Gesamtheit noch kein positives Verhältnis zu dem neuwerdenden Leben gefunden, was für ihre Zukunft verhängnisvoll werden kann, aber sie ist doch so stark vom lebendigen Christuswirken durchzogen, daß man blind sein müßte, wenn man ihr als Gesamtheit das Leben absprechen wollte. Freilich ist das Lebendige in ihr zu ausschließlich persönlich gefaßt. Im Großen - Ganzen bleibt es bei dem ringen um das Einzelheil; nur in seltenen Fällen wird der urchristliche Ausblick auf das umfassende Wirken Gottes, auf das Kommen seines Gottesreiches gewonnen. Nur selten wagt man es, die persönlich ernstgenommenen Worte Jesu ihrem Geist und Sinn nach auf die Gesamtheit der Lebensbeziehungen anzuwenden; aber es ist vielfach gerade die Angst vor Gesetzlichkeit und vor bloßem Moralismus, die diese oft schwächliche Beschränkung auf das eigene Heil in der innerlich erfahrenen Gnade zur Folge hat. Ich wende mich deshalb ebenso entschieden gegen das soeben erwähnte Urteil

- - -

Karl Udo Iderhoffs in den "Erfurter Führerblättern", Frühjahr 1920, wie gegen so manche Urteile, die augenblicklich gegen unsere sog. Christlichen Jugendvereine beliebt werden. Man kennt unsere Jünglingsbündler und christlichen Vereine junger Männer und unsere Gemeinschaften nicht, wenn man in ihnen die moralische Tendenz als das Wesentliche ansieht. Gewiß, soweit sie moralisierend wirken, sind sie ein Hindernis des befreienden Christusgeistes, und manche von ihnen sind gewiß dem Erstarrungsprozeß verfallen, sodaß sie mehr Form und Tradition, mehr Moral und Autorität vertreten als den freien Geist, der alles auf Gott stellt, und alles Christus machen läßt. Gewiß tritt die Ehre Gottes und das gewaltige Heranschreiten des Reiches Gottes vielfach hinter die zu kleinlich gehaltene eigene Seele zurück. Aber man muß die starken Zeiten der ersten Liebe in den christlichen Vereinen junger Männer und in manchen innerlich befreiten Gemeinschaftskreisen erlebt haben, um zu wissen, daß dort wirkliches Leben und oft mannigfaltiges, reiches Leben aus Gott und auf das Reich Gottes hin vorhanden ist.

Für die neue Jugend wird es von Bedeutung sein, ob sie zu einem positiven Verhältnis zu dem Lebendigen gelangen kann, das hier und das in Vereinen und Vereinigungen, in Gemeinschaften aller Art und auch in Kirchen zu finden ist. Die Freiheit von der alten Form, die Befreiung von allem Unwahren und Unechten der äusseren Autorität und Tradition vermag sich wohl mit Achtung und Anerkennung aller auch anderartigen lebendigen Gotteswirkungen zu verbinden, wie die urchristliche Freiheit immer die Verschiedenartigkeit der Geistesgaben betont hat. Aber das steht fest: In irgend ein knechtisches Joch, in irgendeine Behinderung des innerlich drängenden und pulsierenden Lebens kann sich die heutige Bewegung nicht mehr fangen lassen. Sie ist und bleibt revolutionär im Sinne eines wirklichen Aufbaus des Neuen.