In the Lord’s Prayer, Jesus calls on God, our Father, that his primal will should alone prevail on earth, that the future age in which he alone rules should draw near (Matt. 6:10). His being, his name, shall at last be honored because he alone is worthy. Then God will liberate us from all the evil of the present world, from its wickedness and death, from Satan, the evil one now ruling. God grants forgiveness of sin by revealing his power and his love. This saves and protects us in the hour of temptation, the hour of crisis for the whole world. In this way God conquers the earth, with the burden of its historical development and the necessity of daily nourishment.

However, the dark powers of godlessness pervade the world as it is today so strongly that they can be conquered only in the last stronghold of the enemy’s might, in death itself. So Jesus calls us to his heroic way of an utterly ignominious death. The catastrophe of the final battle must be provoked, for Satan with all his demonic powers can be driven out in no other way. Jesus’ death on the cross is the decisive act. This death makes Jesus the sole leader on the new way that reflects the coming time of God. It makes him the sole captain in the great battle that will consummate God’s victory (Heb. 12:1–3).

There is a gulf between these two deadly hostile camps, between the present and the future: between the age we live in and the age to come. Therefore the heroism of Jesus is untimely, hostile in every way to the spirit of the age. For his way subjects every aspect and every condition of today’s life to the coming goal of the future. God’s time is in the future, yet it has been made known now. Its essence and nature and power became a person in Jesus, became history in him, clearly stated in his words and victoriously fought out in his life and deeds. In this Messiah alone God’s future is present.

The new future puts an end to all powers, legal systems, and property laws now in force. The coming kingdom reveals itself even now wherever God’s all-powerful love unites people in a life of surrendered brotherhood. Jesus proclaimed and brought nothing but God, nothing but his coming rule and order. He founded neither churches nor sects (weder Kirche noch Sekte). His life belonged to greater things. Pointing toward the ultimate goal, he gave the direction. He brought us God’s compass, which determines the way by taking its bearings from the pole of the future.

Jesus called people to a practical way of loving brotherhood (Mark 10:28–31). This is the only way in keeping with our expectation of that which is coming. It alone leads us to others; it alone breaks down the barriers erected by the covetous will to possess, because it is determined to give itself to all. The Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5–7) depicts the liberating power of God’s love wherever it rules supreme. When Jesus sent out his disciples and ambassadors, he gave them their work assignment, without which no one can live as he did: in word and deed we are to proclaim the imminence of the kingdom (Matt. 10, Mark 6:7–11, Luke 9:1–6). He gives authority to overcome diseases and demonic powers. To oppose the order of the present world epoch and focus on the task at hand we must abandon all possessions and take to the road. The hallmark of his mission is readiness to become a target for people’s hatred in the fierce battle of spirits, and finally, to be killed in action.

The First Followers

After Jesus was killed, the small band of his disciples in Jerusalem proclaimed that though their leader had been shamefully executed, he was indeed still alive and remained their hope and faith as the bringer of the kingdom.1 The present age, they said, was nearing its end. Humankind was now faced with the greatest turning point ever in its history, and Jesus would appear a second time in glory and authority. God’s rule over the whole earth would be ensured.

The powers of this future kingdom could already be seen at work in the early church. People were transformed and made new (Acts 2–4). The strength to die inherent in Jesus’ sacrifice led them to accept the way of martyrdom, and more, it assured them of victory over demonic powers of wickedness and disease. He who rose to life through the Spirit had a strength that exploded in an utterly new attitude to life: love for one’s brother and love for one’s enemy, the divine justice of the coming kingdom. Through this new Spirit, property was abolished in the early church (Acts 2:42–47; 4:32–37). Material possessions were handed over to the ambassadors for the poor of the church. Through the presence and power of the Spirit and through faith in the Messiah, this band of followers became a brotherhood.

This was their immense task: to challenge the people of Israel in the face of imminent catastrophe, and more, to shake the whole of humankind from its sleep in the face of certain destruction, so that all might prepare for the coming of the kingdom. The poorest people suddenly knew that their new faith was the determining factor, the decisive force in the history of humankind. For this tremendous certainty, the early church gained strength in daily reading of the Jewish Law and Prophets; in baptism, the symbol of faith given by the prophet John and Jesus himself to represent submitting to death in a watery grave in order to be reborn; in communal meals celebrated to proclaim the death of Jesus; and in collective prayer to God and Christ. The words and stories of Jesus and all that they demanded were told over and over again. Thus the original sources for the Gospels and New Testament are to be found in the early church (e.g., Luke 1:1–4).

“Lord, come!” – Maranatha! – was their age-old cry of faith and infinite longing, preserved in the original Aramaic from this early time of first love. He who was executed and buried is not dead. He draws near as the sovereign living one. The Messiah Jesus has risen from the dead and his kingdom will break in at his second coming! That was the message of his first followers, such as Peter, who led the church at Jerusalem at its founding.

The War between Future and Present

God’s new order can break in with all its splendor only after cataclysmic judgment. Death must come before the resurrection of the flesh. The promise of a future millennium is linked to the prophecy of judgment, which will attack the root of the prevailing order (Rev. 19–20). All this springs from the original message passed on by the very first church. There is tension between future and present, God and demons; between selfish, possessive will and the loving, giving will of God; between the present order of the state, which through economic pressures assumes absolute power, and God’s coming rule of love and justice. These two antagonistic forces sharply provoke each other. The present world age is doomed; in fact, the promised Messiah has already overpowered its champion and leader! This is an accomplished fact. The early church handed down this supra-historical revolution to the next generation. Jesus rose from the dead; too late did the prince of death realize his power was broken.2

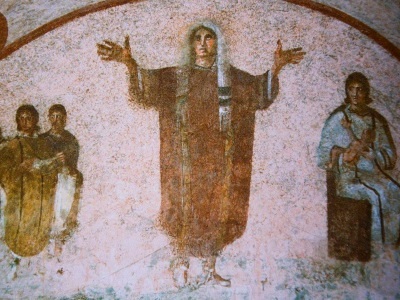

From the time of the early church and the apostle Paul, the cross remains the one and only proclamation (1 Cor. 2:1–2):3 Christians shall know only one way, that of being nailed to the cross with Christ. Only dying his death with him leads to resurrection and to the kingdom.4 No wonder that Celsus, an enemy of the church, was amazed at the centrality of the cross and the resurrection among the Christians.5 The pagan satirist Lucian was surprised that one who was hung on the cross in Palestine could have introduced this death as a new mystery: dying with him on the cross was the essence of his bequest.6 The early Christians used to stretch out their hands as a symbol of triumph, imitating the arms extended on the cross.

In their certainty of victory, Christians who gathered for the Lord’s Supper heard the alarmed question of Satan and death, “Who is he that robs us of our power?” They answered with the exultant shout of victory, “Here is Christ, the crucified!”7 Proclaiming Christ’s death at this meal meant giving substance to his resurrection, allowing it to transform their lives. This transformation proved the decisive fact of Christ’s victory, born of power and giving power, consummated in his suffering and dying, in his rising from death and ascent to the throne, and in his second coming. For what Christ has done he does again and again in his church. His victory is perfected. Terrified, the devil must give up his own. The dragon with seven heads is slain. The evil venom is destroyed.8

Thus the church sings the praise of him who became human, who suffered, died, and rose again, and overpowered the realm of the underworld when he descended into Hades. He is “the strong,” “the mighty,” “the immortal.”9 He comes in person to his church, escorted by the hosts of his angel princes. Now the heavens are opened to the believers. They see and hear the choir of singing angels. Christ’s coming to the church in the power of the Spirit, here and now, makes his first historical coming and his second, future appearance a certainty. In trembling awe the church experiences her Lord and sovereign as a guest: “Now he has appeared among us!”10 Some see him sitting in person at the table to share their meal. Celebrating the Lord’s Supper is for them a foretaste of the future wedding feast.

The Holy Spirit has descended upon them, and grace has entered their hearts. Their fellowship is complete and perfect. The powers of God penetrate the gathered church. Gripped by the Spirit, filled with the Spirit, they become one with Christ. Ulysses, tied to the mast of the ship, sailed past the Sirens unscathed. In the same way, only those who become one with the crucified by being tied, as it were, to his cross, can withstand the lures of this storm-tossed world and the violent passions of this age.11

The trials of all the Greek heroes, however, cannot match the intensity of this spiritual battle. By becoming one with the triumphant Christ, early Christian life becomes a soldier’s life (Eph. 6:10–18), sure of victory over the greatest enemy of all time in the bitter struggle with the dark powers of this world. Murderous weapons, amulets, and magic spells are of no use in this war. Nor will people look to water, oil, incense, burning lamps, music, or even the symbol of the cross to gain victory over demonic powers, as long as they truly believe in the name of Jesus, the power of his Spirit, his life in history, and his supra-historical victory. Whenever the believers found unity in their meetings, especially when they celebrated baptism or the Lord’s Supper and “love meal,” the power of Christ’s presence was indisputable: sick bodies were healed, demons were driven out, and sins were forgiven. As people turned away from their past wrongs and were freed from all their weaknesses, they could be certain of resurrection and eternal life.

Baptism as Military Oath

The equality achieved by faith meant that every believer who stepped out of the baptismal bath was considered pure and holy (1 Cor. 6:9–11). The anti-Christian Porphyry was appalled that one single washing should purify those covered with guilt and evil, that a glutton, fornicator, adulterer, drunkard, thief, pederast, poisoner, or anyone vile, wicked, or filthy in other ways should simply be baptized, call upon the name of Christ, and with this be freed so easily, casting off such enormous guilt as lightly as a snake sheds its skin. “All they have to do is to believe and be baptized.”12 About this forgiveness and complete removal of guilt, Justin says: “Only those who have truly ceased to sin shall receive baptism.”13 Whoever is baptized must keep the seal pure and inviolate.14 Such an incredible practical demand, expecting total change, was possible only by faith in the power of the living Spirit, who descends on the water of baptism and makes it a bath of rebirth, a symbol of new life and purity.… The conviction of the first Christians rested on their deep belief in baptism. Through their faith in the Holy Spirit they were the church of believers that could forgive every sin, because in it every sin was overcome. Many came to the Christians, impressed by the possibility of a totally new way of living and looking for a power that would save them from their unworthy lives.15

More and more soldiers of the Spirit were sworn to this “military oath” through baptism and the simultaneous confession of faith. This “mystery” bound them to sober service of Christ and the simplicity of his divine works. In the water, believers buried their entire former lives, with all their ties and involvements. Plunged so deeply into the crucified Christ that the water could be likened to his blood, they accepted as their own the victory of the cross and its power to sever all demonic powers. Now they could live in the strength of the Risen One. Each believer broke with the entire status quo and was thereby committed to live and to die for the cause embraced through such a consecration unto death. The new time invaded the old with a company of fighters pledged to die, a triumphal march of truth and power.

Love and Economics

During the first two centuries… the movement spread almost exclusively among slaves, freed people, and artisans. The makeup of the membership was reflected in the value the church put on work (1 Thess. 5:12–13). Everyone was expected to earn his or her living and to produce enough to help others in want. All had to work, so that their love could help the needs of others. Therefore the church had to discern and procure labor. This obligation shows how fully the Christian communities shared their work and goods.16 Those not willing to do the work they were capable of – those who were “trading on Christ” – were not tolerated in the communities. “An idler can never be a believer.”17

The freedom to work voluntarily and the possibility of putting one’s capabilities to use were the practical basis for all acts of love and charity. Self-determination in their work gave an entirely voluntary character to all social work done by the early Christians. Hermas gives another indication of the Spirit ruling in the church. He writes that the wealthy can be fitted into the building of the church only after they strip themselves of their wealth for the sake of their poorer brothers and sisters.18 Wealth was regarded as deadly to the owner and had to be made serviceable to the public by being given away. The early Christians taught that just as in nature – the origin and destiny of creation – the light, air, and soil belong to all, so too material goods should be the common property of all.

The practice of surrendering everything in love was the hallmark of the Christians. When this declined, it was seen as a loss of the Spirit of Christ (John 13:35). Urged by this love, many even sold themselves into slavery or went to debtors’ prison for the sake of others. Nothing was too costly for the Christians when the common interest of their brotherhood was at stake; they developed an incredible activity in the works of love.19

In fact, everything the church owned at that time belonged to the poor. The affairs of the poor were the affairs of the church; every gathering served to support bereft women and children, the sick, and the destitute.20 The basic feature of the movement, a spirit of boundless giving, was more essential than the resulting communal life and the rejection of private property. In the early church the spontaneity of genuine love merged private property into a “communism of love.” This same urge of love later made Christian women of rank give away their property and become beggars. The pagans deplored the fact that instead of commanding respect by means of their wealth, these women became truly pitiful creatures, knocking at doors of houses much less respected than their own had been.21 To help others, the Christians took the hardest privations upon themselves (Heb. 10:32–34). Nor did they limit their works of love to fellow believers.22 Even Emperor Julian had to admit that “the godless Galileans feed our poor in addition to their own.” 23

According to Christians, the private ownership of property sprang from the primordial sin of humankind: it was the result of covetous will. However necessary property might be for life in the present demonic epoch, the Christian could not cling to it. The private larder or storeroom had to be put at the disposal of guests and wanderers just as much as the common treasury.24 Nor could anybody evade the obligation to extend hospitality. In this way each congregation reached out far beyond its own community.

But in other ways too, the communities helped their brothers and sisters in different places. In very early times the church at Rome enjoyed high esteem in all Christian circles because it “presided in works of love.”25 The rich capital city was able to send help in all directions, whereas the poorer Jerusalem had to accept support from other churches in order to meet the needs of the crowds of pilgrims that thronged its streets. Within its own city, the relatively small church at Rome gave regular support to fifteen hundred distressed persons in the year AD 250.26 … Christians spent more money in the streets than the followers of other religions spent in their temples. Working for the destitute was a distinguishing mark of the first Christians.

The New Humanity

The rank afforded by property and profession is incompatible with such fellowship and simplicity, and repugnant to it. For that reason alone, the early Christians had an aversion to any high judicial position or commission in the army.27 They found it impossible to take responsibility for any penalty or imprisonment, any disfranchisement, any judgment over life or death, or the execution of any death sentence pronounced by martial or criminal courts. Other trades and professions were out of the question because they were connected with idolatry or immorality. Christians, therefore, had to be prepared to give up their occupations. The resulting unemployment and threat of hunger would be no more frightening than violent death by martyrdom.28

Underpinning these practical consequences was unity of word and deed. A pattern of daily life emerged that was consistent with the message that the Christians proclaimed. Most astounding to the outside observer was the extent to which poverty was overcome in the vicinity of the communities, through voluntary works of love. It had nothing to do with the more or less compulsory social welfare of the state.

Chastity before marriage, absolute faithfulness in marriage, and strict monogamy were equally tangible changes. In the beginning this was expressed most clearly in the demand that brothers in responsible positions should have only one wife (1 Tim. 3:2). The foundation for Christian marriage was purely religious: marriage was seen as a symbol of the relationship of the one God with his one people, the one Christ with his one church.

From then on, a completely different humanity was in the making. This shows itself most clearly in the religious foundation of the family, which is the starting point of every society and fellowship, and in the movement toward a “communism of love,” which is the predominant tendency of all creation. The new people, called out and set apart by God, are deeply linked to the coming revolution and renewal of the whole moral and social order. It is a question of the most powerful affirmation of the earth and humankind. Through their Creator and his miraculous power, the believers expect the perfection of social and moral conditions. This is the most positive attitude imaginable: they expect God’s perfect love to become manifest for all people, comprehensively and universally, answering their physical needs as well as the need of their souls.

And What Now?

Despite all later deviations from the early time of revelation, no church or sect in Christendom has ever completely forgotten that love remains the supreme sacrament of faith, the treasure of the Christian faith.29 Bearing in mind the radicalism of all sects, the narrowness of all monastic exercises in devotion, and the vast responsibilities of the organized churches, Irenaeus was right in saying, “It remains, as in the time now past, that the greatest is the free gift of brotherly love, which is more glorious than knowledge, more marvelous than prophecy, and more sublime than all other gifts of grace.”30

In the fire of first love, in the many signs of God at work, the rich, primitive force of the early Christian spirit continues to speak to us. All the moments of power and truth characteristic of New Testament Christianity can be sensed here, as well as the roots of developments that later led to the organized churches. A clearly defined way of life and faith arises from the manifestation of God in early Christian times. It continues to be a living force today in spite of rigidity in later centuries. Because it comes from the wellspring of living truth, this way can never be achieved merely through external imitation.

There is only one criterion for this way: the direct, spontaneous testimony which the Spirit himself brings from God and from Christ. It is the witness of faith, speaking to us from apostolic and prophetic experience. The original witness of the church must lead us all, placed as we are today in very different camps, into the unity and purity of the clear light. The period of original revelation must be the point of departure for any dialogue between the many churches, sects, and movements of our own day. The awakening and uniting of all who truly desire to follow Christ, so much needed today, will be given at the source, and nowhere else.

Adapted from Eberhard Arnold’s book The Early Christians: In Their Own Words (Walden, NY: Plough, 2015).

Article edited for length and clarity. View original document here: Die Ersten Christen (The First Christians).

Notes

- The first disciples gave witness to the cross, the resurrection, and the future kingdom, and showed that through love, the power of the Holy Spirit could overcome the power of private property and heal people. The Acts of the Apostles, especially chapters 2–4, describes this decisive manifestation of the church.

- Ignatius, Letter to the Ephesians 19:3.

- The same words are used in Acts of Peter 37: “The cross of Christ, who is the Word stretched out, the one and only, of whom the Spirit saith: For what else is Christ, but the Word, the sound of God?” See also Acts of John 94–95, 98–99.

- Ignatius, Letter to the Smyrnaeans 1–3.

- Origen, Against Celsus VI.34.

- Lucian, On the Death of Peregrinus II.

- The Syriac Testament of Our Lord Jesus Christ 1:28; the Arabic Didascalia (Chapter 39, where it is introduced as mystagogia Jesu Christi ).

- Ode of Solomon 22.

- See the Liturgy of James and the Liturgy of Mark. See also the so-called “Clementine Liturgy” in the Apostolic Constitutions and the Syriac Testament of Our Lord.

- The Armenian Liturgy, the Apostolic Constitutions VIII, Clementine Liturgy, after Psalm 118:26.

- The comparison between those tied to the cross (the Christians united with the crucified one) and Ulysses appears in very early Christian art and writing.

- Macarius Magnes, Apocriticus IV.19, in Porphyry, Against the Christians.

- Justin, First Apology 61.

- Second Letter of Clement 6:9. “What assurance do we have of entering the kingdom of God if we fail to keep our baptism pure and undefiled?”

- Cyprian, To Donatus 3–5.

- Didache 12:2–5.

- 2 Thess. 3:6–15. See Didascalia 8.

- Hermas, The Shepherd 14:5–6, 17:2–5.

- The pagan Lucian, in The Death of Peregrinus 13, describes how the Christians rallied to support one of their number when he was imprisoned.

- See Justin, First Apology 67.

- Macarius Magnes, Apocriticus III.5, Porphyry Fragment 58.

- See Didascalia XIX: “That it is a duty to take care of those who for the name of Christ suffer affliction as martyrs.”

- Julian, To Arsacius.

- Tertullian, To His Wife II.4.

- Ignatius, Letter to the Romans, Salutation.

- Bishop Cornelius in Eusebius, Church History VI.43.

- One could agree to a Christian’s right to hold a high office in which he was empowered to adjudicate over the civic rights of a person only if he did not condemn or penalize anyone, or cause anyone to be put into chains, thrown into prison, or tortured (Tertullian, On Idolatry 17).

- Tertullian, On Idolatry 12: “Faith does not fear hunger.”

- Cf. Tertullian, On the Prescription of Heretics 20.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies IV.33:1, 8.