“Light and Fire” is the first chapter of volume four of Inner Land, Fire and Spirit. Notably, a copy of this chapter was printed and sent to Hitler in November 1933. A week later, the Bruderhof was “stormed by 140 to 160 uniformed men,” including SS and Gestapo officials, in a raid that lasted from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.1

Arnold begins this chapter by outlining the darkness that has plagued human existence throughout history in the form of catastrophe and injustice. Lamentably, “faced with the daily suffering of masses of people, the human spirit has proved throughout to be cold, indifferent, and insensitive, no matter what appalling depths the misery reaches” (1). Only light beyond the darkness is able to help humanity out of it, and faith is needed to receive this light. But the light is also painful, since we have grown accustomed to the darkness.

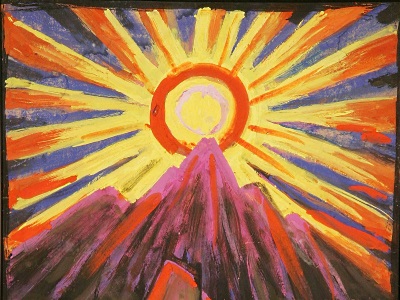

Light is the first major theme of this chapter; the other is fire. For Arnold, fire entails both judgment and salvation. Importantly, fire is a gift from God. Arnold is not referring to fire in its literal sense, though there are points in the chapter where this is true as well, but symbolically, primarily as a force for purification and salvation. God’s fire is given to Jesus, and he imparts it to us in the Holy Spirit to burn away our old selves and make us new. Yet Jesus is to be distinguished from the Greek mythological figure of Prometheus, who acquired fire in his “sacrilegious theft” from “a jealous deity” (2).2

The dual nature of fire as something that both judges and saves comes to the fore in Arnold’s account of early human history. This warrants a brief comment. Particularly from the nineteenth century on, there was an explosion of research in this area, driven by archaeological discoveries, colonialism, increased contact with non-European peoples, and the development of new academic disciplines. Fresh studies were eagerly received by the reading public. This is the context in which Arnold’s discussion of fire in human history appears. Some of the claims he makes depend on scholarship that is now dated and overly speculative. Nonetheless, his historical claims are largely incidental to his understanding of fire as a symbol of God’s judgment and salvation.

Arnold begins with the early human encounters with fire in its raw form, which modern people are often shielded from: “The fires of heaven and the fires of the deep” – lightning, volcanoes, and forest fires – wrought great destruction on the landscape and “filled early man and all creatures of the earth with shuddering awe” (3). One day, fire would result in unimagined benefits for people. Before this could happen, though, “the flames of its wrath must be revealed as consuming judgment” (3). The same is true in the spiritual life. We must know God’s judgment before we can see his salvation.

Importantly, divine judgment by fire works indirectly, a point Arnold will develop further. That is, “death by fire is not caused by rays from the blazing fire but by the nature of death and darkness – opposition to light and enmity to life” (4). The claim is complemented by a couplet from the seventeenth-century mystic Angelus Silesius: “If eyes are blinded by the sun, / Blame the eyes, blame not the sun” (4). God’s wrath and judgment stem from sin and death’s interaction with God’s nature; they are not inherent aspects of his nature.3

Following this, Arnold returns to the theme of light and reflects on its symbolism in the sun. Indeed, Jesus is the sun who shines into darkness. His light is so bright that Paul was blinded by it, though “in three quiet days of earnest prayer, his inner eye was opened to the sunlight of the church of Jesus Christ” (5). For Arnold, “eyes are made for light” (5), but their capacity to perceive light at any given time depends on their level of exposure and adaption to it. The impressive eyesight of Plains Indians and desert Arabs, for example, can be attributed to the high levels of light in their environment.

The sun is immensely powerful. It illuminates the earth from 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) away, a distance we cannot even begin to appreciate. Yet the light emitted by other celestial bodies such as Rigel and Capella greatly exceeds that of the sun, and millions of other stars fill the sky as well. For Arnold, this unfathomable power serves to point us to Jesus, in whom “a fiery light infinitely stronger than all suns put together draws near to the earth” (6).,Understanding the power of the sun can thus help us understand the nature of God. Just as only a fraction of the sun’s heat and light is needed to sustain all life on earth, and without it, life would perish in the cold and dark, so it is with God.

This power of the sun, and its terrestrial complement, fire, explains why different human cultures have often seen it as a symbol of the divine, sometimes even worshipping it. Arnold finds evidence for this reverence in ancient Egypt and India, as well as among ancient Nordic4 peoples. From these experiences, humans began to associate light, warmth, unity, love, and beauty with the divine. And the opposite of light, the dark and the cold, became a symbol of human suffering. The cycles of night and day, winter and summer, provided an image of the human hope for a final summer at the end of time that would put an end to all evil and death.

This brief comment on early human experiences allows Arnold to return to his discussion of humanity’s first encounters with fire. While people were certainly terrified by forest fires and volcanic eruptions, these also provided opportunities for warmth and protection. “So man learned to combine his terrible fear of fire with a reverent thankfulness, for here he encountered an element that united the wrath of a destructive power with the loving gift of life” (13). Indeed, this gift of fire is one thing that separated human beings from animals.

Fire did not just enable the cooking of food or the provision of warmth and protection from predators, though. “True to his origin and his goal, man as fire giver and fire borrower proved to be a communal being. Fire united people in mutual help” (14). That is, fire could be shared with other groups, and it was also an early focal point for all manner of community activities. As such, it was “a sign of the new humankind” (14) and therefore already an indication of God’s redemptive work at this early stage in human history. Moreover, it was through fire that human beings regained some “mastery over the forces of nature” (15) in keeping with their original design in the garden. For Arnold, then, fire is not only a symbol of the judgment and salvation in encountering God but also, in its literal sense, something that has played a key part in humanity’s judgment and redemption.

Because of its power and benefits, fire held a central place in early human society. Like the sun, it assumed profound religious significance so that people “wanted to keep the warm glow of the fire alive through the sacrifice of wood” (14). Arnold even argues that houses evolved out of a need to protect the sacred flame from the elements. The other benefits of houses, like warmth and protection, were already provided by the fire itself, making housing redundant outside its ability to protect fire. While the exclusive nature of Arnold’s claim overly simplifies the likely historical reality, the basic insight that fire played a determinative role in the development of housing is sound and further illustrates fire’s role in redemption history.5

Arnold proceeds to a more detailed account of the relationship between fire and community – or the unity of humanity. In addition to providing a focal point for the social group, its religious significance extended to land use and food distribution: “the fields and pastures consecrated by fire were under the communal management of the whole tribe or village” (20). And fire meant the dead, too, remained a part of the community: “they were not to be left cold and hungry in a dark grave” (20). Here, then, Arnold relates the history of fire to broader, interrelated themes in his work, namely community, shared property, the communion of saints, and the unity of all humanity. Through fire, God was beginning to restore the human community that would find expression in the church and ultimately in the consummated kingdom.

Throughout Inner Land, Arnold regularly offers implicit criticisms of the National Socialist Party and its ideology. One of the more direct criticisms appears in his discussion of the history of fire, a possible contributing factor in the Gestapo raid on the Rhön Bruderhof. Noting that humans soon learned to make their own fire, Arnold suggests that the ancient symbol of the swastika depicted fire sticks being struck together. Because of the universality of fire, though, the swastika cannot belong to a single human group. This presents a clear challenge to Nazism, which prized the distinctiveness of the Aryan race, with the swastika as its symbol. Keywords from Arnold’s next sentences demonstrate that he obviously has Nazi ideology in mind: “the swastika belongs to primeval man. All his descendants, without distinction of race or blood, have a right to it.6 So it is not surprising that all the Aryan tribes as well as the Phoenicians of Canaan preserved this sign,” including “the Jewish inhabitants of Canaan” (24)!7

Arnold’s short criticism of Nazi ideology comes toward the end of his history of fire. After this, he explores how the institution of animal sacrifice grew out of earlier fire rites. This leads into an extended discussion of fire in the biblical texts, effectively concluding the narrative on fire in human history.

Ancient Israelites performed sacrifices called whole burnt offerings; animals were completely consumed by fire as a sign of human devotion to God. It was thus “not only the most frequent but also the most common and comprehensive sacrifice” (25). Arnold finds examples of this imagery used by New Testament authors to interpret Jesus’ death on the cross.8 In particular, he establishes a connection between the completeness of the burnt offering – unlike other sacrifices, there were no parts left over for the offerer or priests – and Jesus’ sacrifice unto death. In the same way, Jesus’ followers are to give themselves completely to God, even if it costs them their lives. Arnold also discovers a connection between the simplicity of the Israelite altar and that of Christian sacrifice, which should be conducted “without the artificial embellishment of human skill and its sham riches, in the primal simplicity of humanity at its poorest and simplest” (26).

Besides sacrifice, fire is used throughout the Bible in close connection with God. Arnold’s discussion of sacrifice ends with a series of quotes from Isaiah that illustrate this relationship. And the dramatic confrontation between Elijah and the prophets of Baal that is narrated in 1 Kings 18 can be understood as a “battle between the fire-gods and the fire coming from God” (27). It is not the fire itself but the God who creates it that is sovereign. Moreover, in Genesis 15, it is not human agents but fire, symbolizing God, that is used to seal the covenant with Abraham. Other examples include God’s guidance of Israel with smoke9 and fire in Numbers 9, his use of fire to appear to Moses, and the fire that characterizes God’s word for Jeremiah.

Next, Arnold attends to the relationship between fire and judgment: “The fire of God’s light never appears without the judgment that consumes what is old, what is withered and dried up, what is lifeless, disunited, and unjust” (29). In this way, God’s fire judged Sodom and Gomorrah, Egypt, and Korah and his followers, just as it will do in the final judgment. But unlike humanity’s historical encounters with fire, this end-time fire will not have a dual nature. There will be no blessing, only judgment. Indeed, this fire “burns with lurid flames and belongs to the nocturnal powers of darkness” (29). Nonetheless, there is still hope for salvation in the present through Jesus.

In Jesus, we encounter the true fire and sun of God. And unless we receive him, we only experience this saving fire as judgment. But because God’s judgment has come to an end in Jesus, his disciples can no longer call down fire on their enemies. Rather, “the burning fire of Christ’s followers shows itself in their fiery mission of love, in the glowing light of their joyful message” (31). The fire in this mission is the Holy Spirit, given by Jesus, restoring the flame lost by Adam.

As he describes the spiritual fire that comes to us in Jesus, various echoes from Arnold’s history of fire can be heard. Jesus’ fire liberates people “from all bestial and infernal powers of night” (32). It brings them together in community around the Crucified One as a fellowship that extends to those no longer on earth. Like early humans, members of Jesus’ church are to share everything they have and do. The divine fire that constitutes the center of their community is given to others in mission and will one day unite the whole world. And, alluding to the purity of fire in the Old Testament,10 the fire Jesus gives cannot be mixed with “alien flames” (34); otherwise it will go out in that particular place. This not only includes human works in place of faith but “the emotional enthusiasm of blood, which is demonic” (35), likely a reference to the Nazi ideology of racial purity.

Arnold proceeds to the place of fire in early Christianity, giving particular attention to the “fire-virgins” who carried flames and wept for the sins of the church (36). This recalls the relationship between virgins and sacred fire in non-Christian societies that Arnold explored earlier (e.g., 21, 23). Early Christians also placed emphasis on Jesus’ future coming and the expectation this entailed. Importantly, people believed that suffering and death, especially “the fire-baptism of martyrdom” (38), prepared them for Jesus’ arrival. Arnold connects this belief to John the Baptist’s claim that Jesus would baptize with fire and to the biblical image of spiritual purification by fire.

In addition to fire, Jesus’ light is central to our relationship with him. This light was already known in the Old Testament, but it has been made alive in the church, with Jesus dwelling in each Christian and driving away the darkness. Arnold takes this opportunity to address a misunderstanding of God’s light as represented by the mystic Mechthild of Magdeburg. This light should not be sought in its “refractions and reflections,” as Mechthild teaches, but “we must dare to look the shining sphere straight in the face” (42) – an obvious analogy to looking directly at the sun, harmful with regard to the physical sun but necessary with regard to the spiritual. Arnold also alludes to Paul here: “the Spirit searches everything, even the depths of God” (1 Cor. 2:10). We can know these depths, not just the surface, because we have been given the Spirit.

After this, Arnold returns to the theme of God’s judgment, explored earlier in this chapter. He follows the Hutterite view that God’s wrath has come to an end in Jesus but remains active outside of him. As such, Christians cannot act as agents of God’s judgment; they cannot seek revenge, violence, or legal action. But because not everyone’s hearts have changed, because evil still runs rampant, God allows human governments to mete out punishment. Arnold again explores the relationship between God and his wrath, this time drawing on an insight from Jakob Böhme, summarizing the mystic’s thought with the words: “God is love and wrath, light and fire, yet he calls himself God according to the light of his love alone, not according to his wrath” (47). This recalls Arnold’s earlier claim that God’s wrath arises out of evil itself and not something in God’s being.

In Jesus, however, there is no wrath. His light animates the life of the believer, and it extends to all nations through human messengers, “triumphing over all the consequences of God’s wrath and hastening to all lands met by it” (51). At this point, fire and light are used almost dichotomously, corresponding to God’s wrath and love, respectively. Arnold writes, “If there were no fire, no light would be given” (49), and he observes of human beings, “the right hand wants to enter into the majesty of light, and the left hand wants to stay in its original state – fire” (51). Moreover, Arnold claims, “Only in the strength of light is he called God” (49), making an implied contrast with fire. At the same time, however, judgment does not exhaust the symbolism of fire, so Arnold can speak of the “fire of love” that brings joy to the heart (50), and fire carries other positive associations in the chapter, as discussed throughout. There is a subtle distinction in Arnold’s fire symbolism, then. On its own, fire can represent both God’s judgment and salvation. When paired with the symbol of light, though, Arnold associates it more exclusively with judgment.

Despite this strong contrast between light and fire, however, “all human beings have both within them” (51). As such, people need to decide between the two: “the soul can burn with the light of love or with the fire of wrath” (51). Nonetheless, choosing the light and being guided by the Holy Spirit doesn’t mean that believers won’t encounter wrath. Their bodies still suffer in a world subject to God’s wrath; they just do not take up an active role in this, renouncing participation in war – and, while Arnold does not explicitly mention it here, in institutions such as the police and government, which are instruments of God’s wrath.

The light of Jesus gives believers a clear vision both of who God is and how to conduct themselves in everyday life. Although they cannot identify themselves with him any more than a plant can identify itself with the sun, there is a special connection here. Importantly, Jesus’ light exposes what was hidden in darkness. In other words, individuals who desire to be renewed by this light must be honest about their sins and not attempt to conceal them, turning to the divine Sun without hesitation.

Arnold concludes this chapter with a reflection on a perennial theme in his work, the unity of the church: “In the church, God lets his thoughts of light be known without deflection” (59–60). As such, “enlightenment through the Holy Spirit has the unmistakable characteristic of leading to complete unanimity, to undisturbed harmony and agreement between all the members of the church of light” (61). In God’s light, his truth is clear and thus the foundation for a unified church.11

Continue:

Introduction

1.1. The Inner Life

1.2. The Heart

1.3. Soul and Spirit

2.1. The Conscience and Its Witness

2.2. The Conscience and Its Restoration

3.1. The Experience of God

3.2. The Peace of God

4.1. Light and Fire

4.2. The Holy Spirit

5.1. The Living Word

1. Emmy Barth, An Embassy Besieged: The Story of a Christian Community in Nazi Germany (Cascade, 2010), 98–103. See the corresponding series that follows Barth’s book. Barth emphasizes the role of the Bruderhof response to the November 1933 plebiscite as a major factor leading to the raid (95–98). For “Light and Fire,” see pp. 49–50, 88–89. Cf. Markus Baum, Against the Wind: Eberhard Arnold and the Bruderhof, ed. and trans. by the Bruderhof Communities (Plough, 2002), 215–16.

2. In the Enlightenment, Prometheus became a positive symbol of human emancipation from religious tradition or even God, as in Goethe’s “Prometheus” (1772–74).

3. It is difficult to communicate the significance of this claim because Arnold tends to avoid discussions that are too deeply metaphysical, in keeping with his intended audience. But if God’s wrath belonged to his nature rather than being a response to sin and death, it would exist independently of creation and therefore be a feature of his eternal being – that is, there would have to be some kind of wrath in God before creation, compromising theological claims regarding his eternal goodness.

4. In this context, a synonym for “Germanic.”

5. Arnold finds additional evidence for this in etymology: “The words for fence (Zaun in German), town (tun in Old English), enclosure (tún in Old Norse), and fortress (dún in Old Irish), with their common Nordic [i.e. Germanic] root, point to the fire and the buildings around it” (19). Here too, though, it is unclear whether Arnold is relying on an individual author or synthesizing material from different sources. As such, it is difficult to determine whether he is claiming these words share a common root – the most literal reading of the sentence – or just conceptual similarities – a more plausible claim (Zaun and Hof both carry an etymological sense of enclosure, for example).

6. Consider Markus Baum’s comment, though: “Today this argument has no more than theoretical value. The crimes of the National Socialists have made the swastika an enduring symbol of terror, murder, and megalomania. Any other interpretation is out of the question.” Baum, Against the Wind, 289 n.25.

7. Compare e.g., Hitler’s explanation of the Nazi flag: “In red we see the social idea of the movement, in white the nationalistic idea, in the swastika the mission of the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man, and, by the same token, the victory of the idea of creative work, which as such always has been and always will be anti-Semitic.” Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Houghton Mifflin, 1998), 496–97, emphasis original.

8. While there are no explicit allusions to burnt offerings in the sacrifice imagery used for Jesus’ death, the New Testament authors did draw on a range of different sacrificial traditions and often blended them when depicting Jesus’ death as a sacrifice.

9. Typically “cloud” in German and English Bible translations.

10. “No ‘alien’ fire was allowed on the altar” (26), perhaps a reference to Lev. 10:1–2.

11. Arnold does not expand much on this beyond establishing a connection between God’s light and the church’s unity. See this article for some other aspects of his understanding of church unity.